Muhammad Abduh and the Educational Roots of Liberal Cosmopolitanism

Muhammad Abduh and liberals today share something peculiar in common: a belief in "diversity" that hinges on a narrow experience and understanding of education.

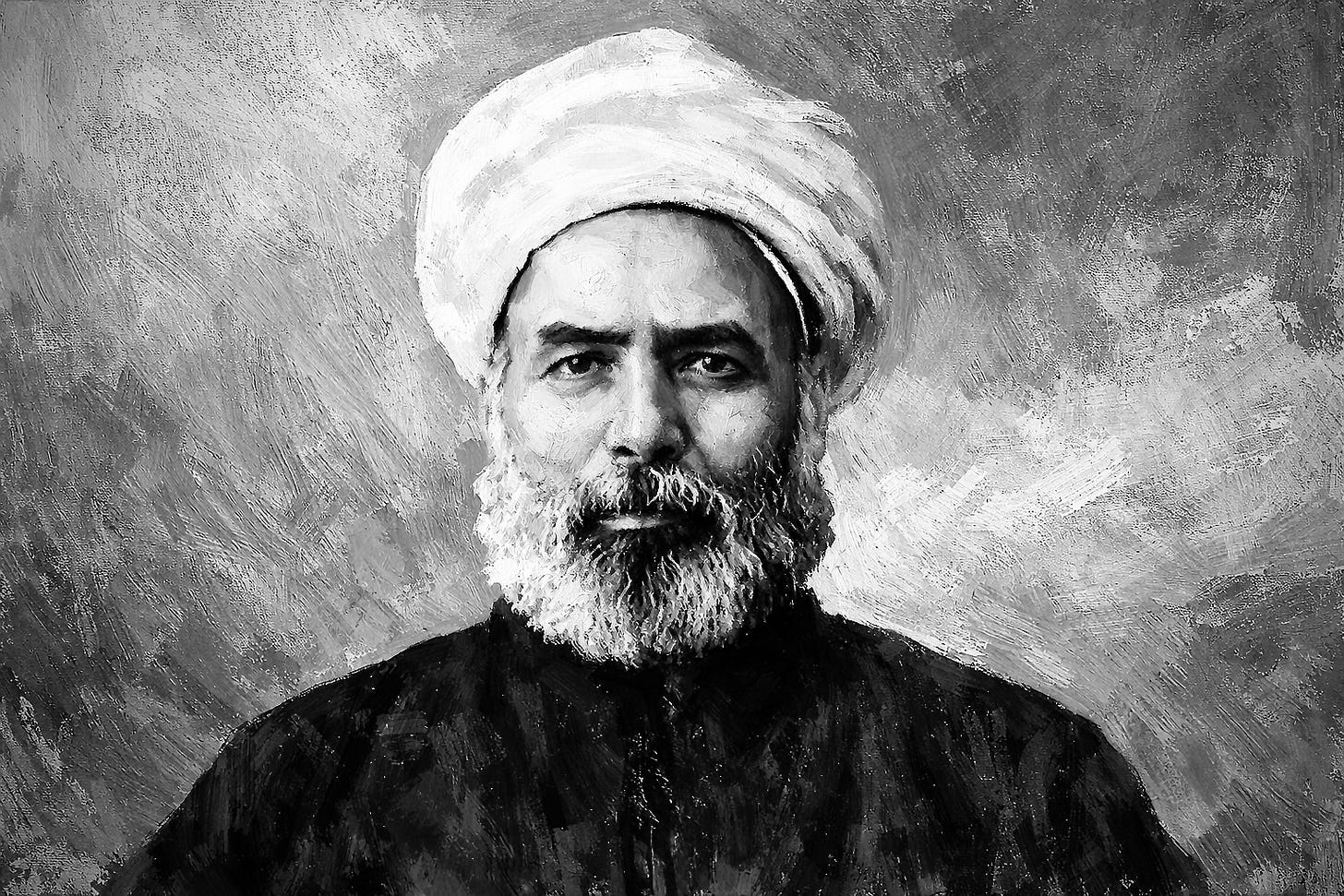

The social reformer and intellectual Muhammad Abduh (1849-1905) was an unconventional evangelist for his religious tradition. In 1897, Abduh remembered giving a lecture in Beirut in the 1880s, where he said: “Islam removed all racial distinctions and affirmed the dignity of all in connection to God in their creation,” adding that all of humanity shared in “the dignity of attaining the highest achievements that God set out.” By “achievements,” Abduh meant knowledge, and the context of his remarks was a school known for its controversial aspiration to educate children of all backgrounds together. Though Abduh’s remarks about mixed schooling are particular to his own time and context, the confrontation between the idealism of diversity and its opposition is familiar to ours.

Abduh was a leader of a cosmopolitan progressive reformist movement that aimed to reject prejudice and chauvinism to realize a new human community united through a love of knowledge. His late-nineteenth century vision is an early example of the progressive ecumenical humanism that has become the ideology widely shared by the educated classes around the world today. It is this ideology that now seems so threatened by an equally-global trend of national populism. Scholars and observers have analyzed “educational polarization” in terms of factors that are specific to the Global North in the twenty-first century, but here I argue that educational reform and the love of a very narrow form of diversity are linked at a historically deeper level. Like Abduh in the nineteenth century, liberals today have not considered how their broad ideals of diversity and inclusion depend on the much narrower range of experiences they possess as members of the educated classes. Simply put, the diversity with which educated professionals are most comfortable is the diversity of people who have shared this same experience.

Education and Belonging

Pundits, political scientists, and casual observers have commented extensively on educational polarization in Euro-American politics. Most important here is the trend of left-liberal political parties increasingly relying on the votes of educated professionals as much of their traditional working-class base has embraced the right and far-right. Thomas Piketty among others illustrate that though this trend is pronounced, it is not as simple as the left going upscale and the right representing the downtrodden uniformly. It is rather that parties like the Democrats and Republicans have become idiosyncratic cross-class coalitions organized around cultural issues. Though every country’s culture wars are different, voters across the Global North have grown more opposed to immigration from poorer countries as educated professionals have embraced diversity as a core value.

This preference among educated liberals has significantly shifted politics as a whole. Beginning in the 2010s, long-term intramural academic debates about the humanities canon and the social bases of prejudice spilled over from college campuses to major metropolitan media in the United States. The New York Times and Atlantic were debating the definitions and salience of terms like “intersectionality” and “systemic racism,” with professors as likely to appear on their podcasts as politicians. Whether or not metropolitan liberals have undergone a genuine moral transformation in recent decades, anti-xenophobic and pro-diversity rhetoric has certainly prevailed in their spaces.

The media also fractured such that in the early twenty-first century, it was possible for people to only consume print, audio, and video that reinforced their political views and cultural tastes. With their hegemony over the media, metropolitan left-liberals were especially able to surround themselves with images of people of all backgrounds and identities sharing an urbane and convivial lifestyle. This tendency in culture and politics both enabled educated people’s low-stakes love of apparent difference and masked a major driver of their uniformity.

As universities in the United States and Europe increasingly relied on the tuition of international students and faculty with global expertise, diversification was visibly realized across college campuses and among educated professionals. However, where doctors and professors may differ by ancestry, religion, or family structure, they have one very deep similarity, which is the experience of succeeding in educational institutions and an identification with their mission. The professional-managerial class (PMC), with its reliance on academic, technical, and professional credentials, favors people with not only intellectual gifts but the social adroitness to manage their professions’ political economies, which interconnect collaboration and competition. To add to this mix, PMC culture’s defining ideal, namely “the pursuit of knowledge,” is strongly individualistic and competitive as well as simultaneously collectivist and high-minded. People who succeed in and identify with school education learn to judge themselves and their peers by how well they achieve goals they believe to confer both personal honor and social good. So while such people are indeed part of a community with diverse backgrounds, it is also true that the mission-oriented identities they acquire in graduate school or professional offices can override the salience of the differences with which they originally came.

Historically, this sensibility took root among the educated classes when nineteenth-century progressive reformers all over the world sought greater harmony in diversity through common schooling. Benedict Anderson has canonized the idea that in the nineteenth century, people all over the world shrank their imaginations of community down from expansive kingdoms of gods into narrow nation-states. Classical historians like Albert Hourani and George Antonius have shown us how the accommodating Ottoman Islamic vision gave way to a partisan politics that pitted Arab against non-Arab, neighbor against neighbor. However, the late nineteenth century was also a time of a reinvigorated imaginary of cosmopolitanism and inclusion as people and media traversed the globe and connected with each other in new ways. This is apparent, for example, in the way ulama, intellectuals, and Ottoman leaders sought to secure Muslim self-rule and cohabitation by speaking of many different ideals to different audiences. It is equally apparent in Abduh and his interlocutors, who made their appeals for unity in the great nineteenth-century idioms of nation, empire, language, race, science, religion, tradition, and progress.

Abduh’s Vision of Unity

Scholars, critics, and even Abduh’s own friends have disagreed about how successfully the reformer and activist kept his ideas consistent and focused. However, Abduh’s vision of inclusive knowledge-seeking becomes very clear when his life as an educator is in view. Few of Abduh’s views about politics, theology, or Islamic law found much assent in his lifetime or since. Yet a generation of social reformers all came to believe that universal education could simultaneously instill a love of learning and respect of differences just as Abduh imagined.

Where Abduh, the ulama, and politicians worried about how Muslims could adapt new technology and organizations to secure their fortunes and autonomy, ordinary parents also wanted their children to get ahead in a changing world. In Beirut, Christian missionary schools drew students across confessional lines even as they made evangelism a central part of the curriculum. In the 1880s, Abduh joined other Muslim educators in al-Madrasah al-Sultaniyyah (the Sultanic School), a private institution established to respond to the missionary challenge with ecumenical outreach and progressive pedagogy supported by the Islamic Benevolent Society. At the prompting of his brother, Abduh wrote up his lectures at the Sultaniyyah as risalat al-tawhid (Treatise on Unity).

Abduh’s treatise on tawhid has long received attention for its unique attempt to bridge medieval and nineteenth-century cosmologies. In theology, the term tawhid refers to the strict monotheism elaborated by Muslim theologians, but the word also evokes unity more broadly. In his famous essay, Abduh describes an Islamic political unity that requires more than a passive respect for diversity in religion. In an argument that foreign imperialism threatens all native people together, he sees that Muslims have a duty to protect others with all the force with which they protect themselves.

Abduh sees this kind of polity as directed to and cemented by intellectual conviviality. For him, “there is a spirit with which God imbues all his divine laws for rectifying of the intellect and the guide of reflection.” Abduh is saying that though the Quran distinguishes religious communities by different legal instructions from God, its words of guidance all point to the same kind of activity. This for him is the activity of “approaching every question in its right way and inquiring after every object by its causes.” Abduh argues that God enjoins mutuality, even fraternity, among different religious communities and “commands that debates always be undertaken in kindness.” He saw religious debate as a vital part of shared civic life.

Abduh further argues that a contending pluralistic society would best favor the Islamic religion’s universal appeal to reason. It is on this basis that he made his famous statement that Islam is “the first religion to address the rational mind.” In his time and since, scholars and critics have taken interest in how Abduh links nineteenth-century developments in natural sciences to the truth of the Islamic theology of tawhid. However, what stands out to me is not so much how he links science and theology as abstracted conceptual fields, but rather the human activities of learning about them. Simply put, Abduh imagines that people will both evangelize for their own religions and get along with people of others by engaging in the intellectual activities of studying, debating, and inquiring. His vision of a multifaith, intercommunal polity under Ottoman Islamic rule is principally an intellectual one. In explaining this view, he not only generalizes his own experiences as a cosmopolitan scholar, but also imagines that everyone else in society would organize their own lives and relate to others in this way.

It is this aspect that united many ulama and lay people to oppose Abduh in Beirut and beyond. As I have discussed elsewhere, many Muslim ulama who opposed mixed-confession education were not generally concerned with intermixing as such but about how students might develop similar ways of talking, dressing, and thinking that could make it difficult to distinguish Muslims from others. These ulama did not generally share Abduh’s experiences of collaborating with and debating against non-Muslims in such a way where they could share space and purpose, and they did not share his confidence that ordinary believers could do the same without concern about their religious commitments.

As Youshaa Patel has recently elaborated, ulama have long exhorted Muslims to distinguish themselves from others by dress and deportment. Abduh thought no less of this imperative, but in such writings as his infamous Transvaal fatwa, he reconciled this idea along curiously intellectual lines. He rather thought believers’ own minds and hearts sufficed to distinguish them from others. Though I have seen no evidence that Abduh dressed in European fashions, violated halal dietary norms, or socialized with women immodestly, rumor-mongers were able to spread these scandals by drawing on the fact that he was comfortable in others’ spaces. What makes Abduh’s idea of diversity historically distinct is not only that he imagines study and work as multi-faith activities but also that he imagines everyone partaking in them as formative experiences of individual and collective life.

In his famous tawhid treatise and many other works, Abduh generalizes the habits and ethics of scholarship to define a good human life in a multi-faith world. He thus transforms what traditional ulama had seen as a rare virtue into a universal requirement for the good life for all people. Abduh further conceives of this educational exercise as the habituated love of diversity just as liberals today do. However, both visions of inclusion rely on coercion.

Writings by Sultaniyyah students in the early twentieth century reveal a strict and censorious institution defined as much by the military ethic of Ottoman elites as by Abduh’s vision of multicultural inquiry. However, Taha Hussein’s (1889-1973) memoir of more traditional Islamic education reveals a parallel experience of drudgery and anxiety. These kinds of accounts are not unique to their time and place but suggest an experience shared by people in disciplinary institutions. The relatively few students who thrive in these institutions often identify much more closely with those institutions’ rules and attitudes than the majority of others. Similarly, today, the students who grow up and get knowledge-centered professional-managerial jobs (especially if they become educators themselves) have diverse backgrounds, religious commitments, and family structures. However, these diversities mask the commonality of their experience: they thrived in comprehensive conscriptionist schools and, succeeding so well in them, internalized their mission.

Integration and the Educational Divide

Though universal education as a desirable idea took rapid hold in the late nineteenth century, it took considerably longer to realize as an institutional practice. In other words, the classes of people who already experienced and identified with education nearly all assented to universalizing their vision of the good, but the creation and maintenance of inclusive education was considerably more complicated than agreeing with an idea in principle. In a popular critical work on education, Freddie deBoer states that it was not until 1970s that the United States achieved universal elementary schooling. According to him, this is just the moment when talk of a “crisis” of declining standards in academics and discipline became widespread. I would here extend deBoer’s analysis to say that by the late-twentieth century, the reality of public education was finally reaching the people who were the most socioeconomically distant from the classes who conceived the ideal.

Yet for left-liberals, the struggle against segregation overshadows all other parts of the story of educational expansion and its relationship to class and the state. The liberal account claims that white Southerners resisted integrated schooling with a unique pathology, and this account tends to ignore the fact that integration was promoted through coercive federal (and even military) force that left Black students especially vulnerable. When in the late-twentieth century federal authorities ordered busing to desegregate schools in cities like Boston, opposition to institutions that enforced intimacy with strangers was also forceful. Not only were Northern whites as susceptible to racist ideologies as those in the South, they also resisted losing what little local control they had and came to see education and the economic changes it facilitated as leaving them behind.

Although inequality increased dramatically in the late-twentieth century, the results of educational change were not uniformly disempowering. In the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries, higher education consistently expanded, and while the most prestigious and powerful employment sectors like tech and finance have remained the most exclusive, the professions of law, medicine, and academia have become considerably more diverse. It is from this vantage point that I stress that Atlantic liberals are not merely kidding themselves about diversity. College towns and PMC enclaves in cities really are diverse. We who have family, friends, and colleagues who come from all over the world really do structure our lives through genteel, rule-bound competition and collaboration for shared career goals. When populists claim that immigrants threaten our way of life and our future, they are simply not talking to our culture or lived experience.

However, that culture and way of life was shaped through an extremely partial experience, which is flourishing in school. Opinion polls show that few people enjoy or look forward to school. As the perception that people need school to find good jobs has diminished, so has trust in a system that forces people into uncomfortable situations. The people who experience school as a place for peace and growth have more diverse backgrounds than they have ever had, but they are united by support for and comfort in modern educational institutions that are strikingly different from most other people. This cultural gulf is so wide that opposition to educational-reformist ideas of diversity and meritocracy has proven a durable political link between rich reactionaries and precarious majorities of voters.

Two Thoughts on Abduh’s Failures

Instead of looking to Abduh’s failures at promoting mixed education merely to criticize the idea of public schools or promote an alternative model, I conclude with two thoughts on how our educationally polarized politics can learn from his experience. First, although Abduh and likeminded reformists advocated the idea that everyone had to go to school to learn respect for diversity and pride in their own community, they themselves did not come out of such institutions. Rather, Abduh was inculcated in the tradition of Islamic higher education with roots in the Middle Ages that trained the discernment of religious scholars. These ulama came from all over the Islamic world to study in places like Cairo’s 1000-year old Al-Azhar, where Abduh studied. Though Abduh felt a reverential love for as well as a reflexive skepticism toward this curriculum, his belief that inclusion fosters the love of learning was shaped through his narrow experience of the ulama way of life. In this way, we can see that ideals of inclusion and self-respect institutionalized in our education system today are not limited to such a system.

My second thought is the cautionary reminder that the ulama enjoy with Muslim communities an organic relationship of trust and respect that liberal academia and the professional class simply do not have with society broadly today. Though they have tried, through educational coercion and media dominance, to universalize their experience of tolerance and love of learning, they have failed so thoroughly that the broader public in the United States and elsewhere seems poised to reject everything those ideals touch—from competitive elections to the court system—rather than endure more diversity “shoved down our throats.” This is obviously not the time for proponents of equality and solidarity (PMC or otherwise) to retreat from political action, but that action cannot be premised on the belief that the hard work and limited gains most people experience in school will result in a mutualistic love for the truth. Our inspiration from the ambitious optimism of progressive-era reformers like Abduh must also reflect a full knowledge of their partiality and limits.