“Socialists Think”: In Memory of Asad Haider

On socialism, self-criticism, and the end of a political sequence.

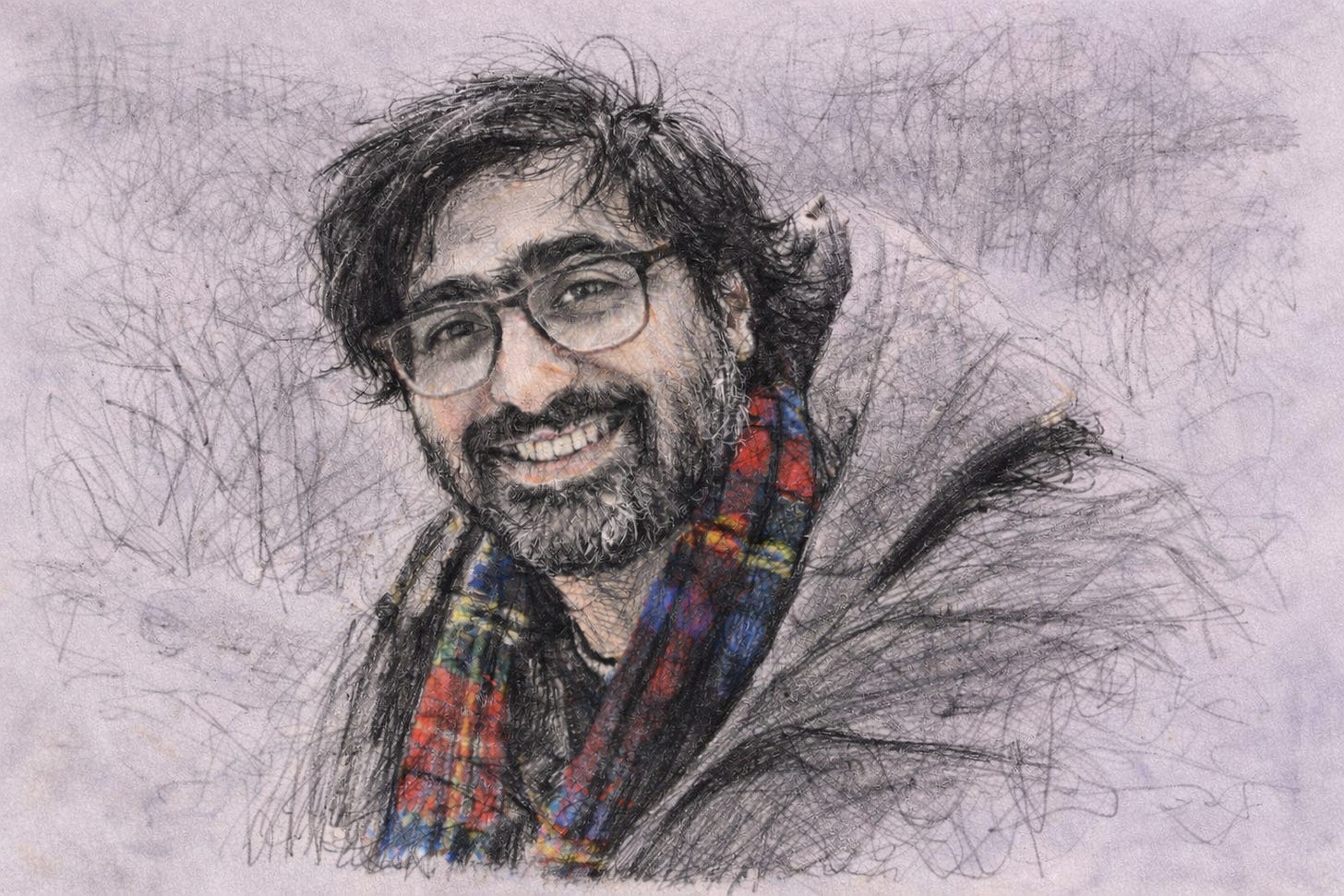

The unexpected death of Asad Haider last November came as a major shock to everyone that was touched by his writing and work. Asad was a couple of years younger than me, but I looked up to him as a mentor. His presence on the left was like a lighthouse that illuminated the limits of our present and called us back to the emancipatory tradition. I first met Asad when he joined my study group on Sylvain Lazarus’ Anthropology of the Name during the height of the George Floyd uprising in the summer of 2020. Still reeling from Covid-related lockdowns, many of us would protest by day and meet at night over Zoom to discuss the thought of this relatively obscure French Maoist. Asad had recently published a best-selling book titled Mistaken Identity: Mass Movements and Racial Ideology,1 a coming-of-age story that documents the travails of his Pakistani Muslim family and the challenges he faced in a post-9/11 world. The book offered a Marxist critique of both the post-racial centrism that emerged in the wake of Obama and the hyper-racial liberalism that seemed to accompany the rise of Trump.

The book drew fiery responses and it catapulted Asad into a spokesperson for his generation. But unlike most political spokespeople who rise to prominence, Asad was different. He had immersed himself so deeply in the Marxist canon that, when he spoke, it quickly became evident that he was a visionary whose political acumen was deep and set on restoring the emancipatory tradition in our time. This seriousness of erudition was only slightly offset by his jovial smile and laid-back demeanor. It was often very difficult to discern much anxiety in Asad when he spoke—his sentences seemed to come together as if he were rehearsing a paper with ease.

What caused me to have immediate affection toward Asad was that, when I first met him, he told my reading group that he was undergoing “self-criticism,” meaning he was re-considering his core views based on the responses his book generated. Asad explained that he was criticized both as “too Marxist” for enveloping race into class, and as “not Marxist enough” for thinking racial struggles could be emancipatory in themselves. The latter critique, he said, was the more influential on his thought and led him to think about what a more comprehensive theory of class would be (although he admitted that such a project was not what the book set out to achieve). The way that Asad responded to these criticisms did not lead him to recoil in passivity, nor did it lead him to double down on his initial viewpoint.

Asad’s self-criticism was akin to the type of self-criticism that his intellectual mentor, Louis Althusser, developed: a self-criticism that led the latter to discover what he called a “new practice of philosophy.” It is rare that an intellectual is elevated to the status of a trusted voice on the left, and when they are, we expect a lot from them. For a short period of time—too short indeed—Asad became the intellectual of our generation; he became a voice for a generation facing unprecedented political instability and fallout from events that overwhelmed our resolve and capacity to mount a fight. We have been defined by 9/11, the Iraq War, the economic crash of 2008, as much as we have sought to mount an offensive through Occupy Wall Street, the Floyd uprising, and Bernie Sanders’ electoral efforts in left populism. Asad developed a method for re-introducing communist thought and practice amidst this chaotic conjecture in which we find ourselves.

Asad completed his dissertation on the problem of political organization coming out of postwar French Marxism from the History of Consciousness program at UC Santa Cruz, the same department which produced American luminaries and political thinkers such as Black Panther Party leader Huey Newton and philosopher Donna Haraway. This area of study gave him a broad mastery in the philosophical renaissance that we know as twentieth-century French philosophy—from leading epistemologists Gaston Bachelard and Jean Cavaillès, to the world-historical philosophers Michel Foucault, Gilles Deleuze, and Jacques Lacan. But Asad’s primary philosophical master was Althusser, the most important Marxist among the postwar French philosophers. To read or listen to Asad was to sense a thinker that had absorbed Althusser’s lessons in such a deep and thorough way that it was evident the latter’s problematic lived on through him and animated all that he thought. Indeed, it was the lineage of Marxist philosophers that emerged from Althusser’s school with whom Asad would most strongly identify.

Next to Althusser, it was Alain Badiou, the prominent French polymath, and his comparatively obscure militant comrade, Sylvain Lazarus, to whom Asad was most drawn. What Badiou offered Asad was the affirmation that emancipatory politics is about the capacity to make a decision on an event which brings about something new. This precise capacity to decide on political activity is what is made to be impossible in the world of capitalism. Badiou’s materialist Platonism offered an alternative to the sense of capitalist realism that seemed to swallow our generation whole. His investigations pointed to historical moments in which groups of workers seized a collective power to break from the inertia of our present.

Lazarus provided Asad with the tools to completely rethink socialist praxis and education. As co-founding editor of Viewpoint Magazine, the open-source journal of Marxist study and politics, Asad and his team curated some of the most important journal issues on key themes and topics in Marxism. One such issue was dedicated to the concept of “workers’ inquiry,” a method through which socialists orient the locus of political activity in the factory and workers’ jobsites, in an effort to generate a politics centered on workers’ demands grounded in their determination and thought. Workers’ inquiry is the best means through which to generate new knowledge of our situation in order to understand and act politically as socialists. Lazarus stands uniquely in the history of Marxism as a thinker who seems to have cracked a riddle that has plagued Marxist and communist practice since the dawn of the socialist movement in the early 1800s. This riddle is found in the dialectic of theory and practice—specifically, in confronting the question: how are the abstract ideas of socialism and communism to be realized in the concrete practical struggles of workers? This is a problem that Marx identified as early as 1843 when he wrote to the young Hegelian socialist Arnold Ruge:

the whole principle of socialism is concerned only with one side, namely the reality of the true existence of man. We have also to concern ourselves with the other side, i.e., with man’s theoretical existence, and make his religion and science, etc., into the object of our criticism.

In this same letter, Marx went on to make a deeply philosophical claim about the origin of ideas and whence they emerge. Lo and behold, Marx’s answer is that ideas do not emerge in the lofty heights of abstract principles of communism but rather out of the existing struggles of this world. As such, Marx stresses that, as socialists, we should not confront the world with “new doctrinaire principles and proclaim: Here is the truth, on your knees before it!” Marx instead argued that, as socialists, we must

develop for the world new principles from the existing principles of the world. We shall not say: Abandon your struggles, they are mere folly; let us provide you with true campaign-slogans. Instead, we shall simply show the world why it is struggling, and consciousness of this is a thing it must acquire whether it wishes or not.

Lazarus’s political thought extends the insight that the young Marx made to Ruge, but on a far more comprehensive scale. This entails developing a method for socialists to inquire into existing sites of struggle to gauge political novelty in a given situation, whether that be a labor struggle at a job site, a protest movement against imperialist war and aggression, or an immigrant justice movement. Lazarus develops a strategy for locating the rational core of novel thinking—thinking that reflects the group’s interior relation to their demands, which is the emancipatory kernel of the group—and elevated it to the level of a new principle for political action. This method implies an entirely new orientation to political education itself in that it reverses the hierarchal pedagogy which tends to force workers to adhere their action to a prescribed idea of political emancipation. Emancipatory politics is not about teaching the proletariat “how to think,” but rather starts with a decision based on this fundamentally egalitarian maxim: “people think.” The consequences from this starting point change everything about how we conduct politics. As Asad remarks in his essay “Socialists Think”:

We can’t possibly know what principles will be active in political situations ahead of time. To know about them in their specificity, we have to conduct investigations which begin from the recognition that workers think. This is an investigation which does not assume we know what workers think, but assigns priority to learning about their thought.

In order to understand Lazarus’s contribution and impact on Asad’s own thought, we must consider the distinction he makes between a relation of thought and a relation to thought. The latter is what Lazarus names “objectal” politics, in which an exterior process dictates the thinking process, hence “to” something outside of its own process. A politics in interiority is one in which a people’s thinking has developed a relation of the real of thought as such. Such a mode of interiority is rare and sequential. Politics in interiority is marked by a collapse of knowledge within a situation, that is, by a collapse of a collective group’s reliance on what Lazarus called “objectal thought.” As Asad concludes in his essay:

Let’s adopt this founding statement in our own internal discussions and the decisions regarding our internal organization. Let’s reject the dictation from above, which provides ready-made answers to externally imposed questions, and instead say: socialists think.

Lazarus’s system is intellectually humbling, and it is no surprise that Asad found in it a wellspring for an entirely new epistemology for militant politics. Based on the insights of Lazarus, Asad also identified two dangers in our political moment: betrayal and nostalgia. What Asad saw coming was the end of a sequence of militant politics, one that was opened by Occupy and which led to the Floyd uprising. He argued that we face the threat of increasing depoliticization that the end of this sequence will inevitably kick up, and warned that the left will increasingly come to see the project of emancipation with a sense of futility and corruption. This is a result of the ending and dissolution of a sequence of politics in which the terms “socialist” and “communist” become reduced to little more than identities whose content is policed—something Asad warned against but was optimistic we could confront.

Above all, it is his sense of egalitarian optimism—so grievously lacking in our time—that ensures Asad’s memory will endure.2

Originally titled Mistaken Identity: Race and Class in the Age of Trump.

Really moving tribute that captures somthing essential about political education. The distinction between teaching workers "how to think" versus starting from the premise that "workers think" flips the whole pedagogical relationship in a way that feels obvious once stated but is rarely practiced. I remember attending union meetings where outside organizers would lecture about theory while ignoring what shop floor workers were already figuring out through thier daily struggles. That disconnect alienates people faster than any anti-union campaign could.