Your Subscription Service Is Not a Community

Corporate-born "communities" are astroturfed projects that fabricate connections and make purchasing power the limiting, necessary, and determining point of access.

“What life have you if you have not life together? There is no life that is not in community.” So wrote T. S. Eliot in a 1934 piece lamenting the modern loss of communal and religious life. Less than a century later, we find words like these deployed to advertise digital platforms like Discord and Slack. We are now seeing—at a dizzying pace—commercial and digital communication platforms utilizing the word “community” to describe what is either a glorified group chat, or a collective of people who pay for a subscription to use a specific service or product. The corporate capture of the term “community” is now so totalizing that its use as a sales pitch no longer strikes us as odd or wrong.

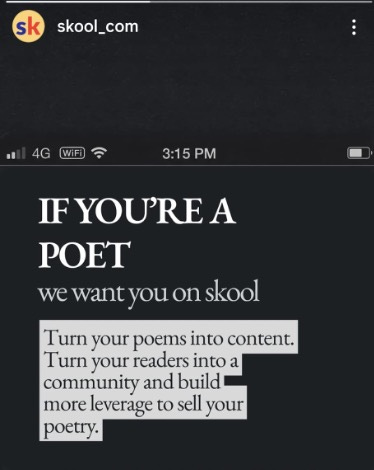

Take the online platform “Skool,” which has been advertising aggressively to me over the past few weeks, after the algorithm discovered I am a poet:

The pretense to “building community” falls completely flat here: this is really about productizing your art (in this case, my poetry) for the content economy and leveraging the feeling of “community” to make money. And while the algorithm continues to feed us ads like this, traditional funding streams and patronage for the arts become smaller every year—the beneficiaries of these old models are now expected to assimilate themselves into the new models that Skool and other similar companies offer as a service.

Notably, Skool’s co-founder, Daniel Kang, signs-off his personal website in the following way:

If you’re building something meaningful, curious about communities, or just want to trade ideas, I’m always open to a conversation.

The curiosity someone may have about communal life—perhaps about schooling, childcare initiatives, or the building of third places—is not what is being referred to here. What is really meant by this seemingly innocuous sentence is that if you want to understand how to monetize a digital service to a group of people with a shared interest, contact this person because he is proficient in the “skill” of delivering “community” to you as a monetizable service. One of the other reasons Kang frames his statement in such a vague manner is that straightforwardly explaining the economic incentives behind it would cause the veil of innocence to fall. Put simply, corporate entities and the people who run them know that speaking plainly about their motives will not work in a culture that is becoming increasingly aware of the brutality of the modern economy.

Lesser-known companies like Skool might just employ soft-toned “community speak” as a marketing strategy, but for corporate behemoths like Amazon and McDonald’s, millions of dollars are invested to convince the public they are wholesome places to work as well as staples of your community. Their aim is to produce heartwarming advertisements to counter stories about union busting and poor working conditions—realities which hinder and harm actual communities. Financially strained workers who chronicle their brutal working conditions in established media outlets can simply be drowned out by the contrived, “positive” advertisements these corporations regularly commission.

But the attempt to soften hyper-capitalism is not limited to ad-washing after, say, a workers’ rights scandal; it is part of a more general trend to convince people that these legal entities pose no threat to the wellbeing of communities in particular and societies at large. This is why we are witnessing an explosion of “community management” roles, which have little to do with supporting or growing actual communities and almost everything to do with managing them for corporate interest and profit. What used to be “client management” or “customer management” is now commonly “community management.”

Take WeWork, the global purveyor of warm and trendy office spaces. The employees hired to maintain relationships with paying customers are, predictably, called “community managers.” They have an entire section on their website called “community stories”—a curated selection of narratives from and about their paying customers. Many of the showcased stories are of companies that are helpful for WeWork’s brand, like someone working on recycling, or the promising developments of some health-tech firm. There is no way of knowing if these types of private enterprises are reflective of their customer base, but the overwhelming likelihood is that they are not. The investment banking giant Goldman Sachs (which incidentally worked on WeWork’s failed IPO) rented a WeWork office in Birmingham, England, but didn’t make the cut for community stories. While it is clear what this kind of “purpose-washing” is for, one has to question if, on some level, these entities are trying to convince themselves as well as us of the fiction they perpetuate.

What Is a Community?

If global group chats between World of Warcraft superfans and companies who rent real estate in the same office building are not communities, then what are? A useful starting point to answer this question is visualizing a physical place—“meatspace,” if you will. Ray Oldenburg’s “third place” thesis is especially useful here. In The Great Good Place, he writes:

Subsequent training in sociology helped me to understand that when the good citizens of a community find places to spend pleasurable hours with one another for no specific or obvious purpose, there is purpose to such association.1

What I find most striking here is the contrast between the lack of a “specific and obvious purpose” in organic communities, and the narrow purposes of modern corporate “communities.” Corporate-born communities are astroturfed projects that fabricate connections through shared “interests” that include purchasing the same brand of drink holder or productivity software, for example. These “communities” have their own broad structural qualities in that they are usually non-physical (members are unlikely to ever meet), formed for a specific reason or interest (contra Oldenburg), and are trapped behind a paywall (thus making purchasing power the limiting, necessary, and determining point of entry).

These structures are exclusionary and promote a kind of endless reclusion into ever-narrower niches that promise “freedom” from the frictions of actual communal life. Put differently, the kind of life that these structures pull you away from are precisely those which force you to confront others with different interests and viewpoints, which is crucial to developing sympathy and empathy. The alternative is being a member of multiple online communities where the frictions of life are attenuated to the satisfaction of their members.

The corporate and digital versions of community are proliferating at the same time that physical community spaces such as libraries are closing down or losing members. As Philip Slater says, “a community life exists when one can go daily to a given location at a given time and see many of the people one knows.” The attraction of online communities, and what they specifically lack, facilitate declining active memberships in more “traditional” communities. Be they mosques, churches, or libraries, the messy humanity of coming up against a foe, or holding the hand of an elder, becomes less likely if we start to exist in our group chats alone.

Gyms, cafes, barbershops, and libraries still exist, and some are even thriving in popularity. These types of institutions are often given as examples of Oldenburg’s third place. However, many of these places, specifically those that are for-profit institutions, are increasingly built around an idea of exclusivity. They promote the flattening, corporate “find your tribe” style of community, which eliminates friction in the same way that online special interest group chats do.

An actual tribe connotes kinship in the literal sense—multiple generations in the same physical area, and ties of blood and honor. This is a far cry from a gym inviting you to “find your tribe” by giving them a recurring monthly chunk of your paycheck. The honor of the other regulars is not your business by design. Take the perfectly named Third Space luxury gym franchise, where memberships start at a tidy £245 ($330 USD) per month. This is on one level a type of third place—neither home nor workplace—but it fails the traditional definition of that term by being inaccessible to the vast majority of people on the basis of social class. It is purposefully elitist in a way that a café in a rich neighborhood that incidentally serves people of the same social class isn’t.

Why Bother?

If humans are social creatures and speaking animals, then a reduction in sociality and speaking to one another is existential. The negative effects of digital communities are compounded further by the degradation of communication brought about by AI. Often, the selling point of these communities is that they connect people from all over the world. But if that connection runs parallel to a reduction in the quality of communication itself, then even the purported benefits will give us ever-diminishing returns.

If all these disparate digital platforms are “hosting” communities, then we cheapen the places where real communality occurs in all its beauty and ugliness. It is impossible not to experience that process of cheapening when your local library closes, or when you can’t leave your children with neighbors while you go to get groceries—all while you’re being promised membership in various “communities” by fan forums on the Internet. The effects of a loss in shared communal place are felt acutely by those who may have grown up with them—to us, it is impossible not to experience this loss viscerally. It is precisely this group or generation that bears the burden of resurrecting communality; those who have grown up without it might not know what they are missing. We need to call out these parasitic entities, plainly expose their subscription businesses for what they are, and allow organic communities to be rebuilt from the ground up. If we don’t—to return to Eliot—we risk not knowing or caring who our neighbors are.

Ray Oldenburg, The Great Good Place: Cafés, Coffee Shops, Bookstores, Bars, Hair Salons, and Other Hangouts at the Heart of a Community (New York: Marlowe & Company, 1999), ix.